The People of “Tent City”

In front of a traffic light between I-794 and Clybourn Street, a woman sat on a white plastic bucket. She held a cardboard sign with the words, “BABY ON THE WAY ANYTHING HELPS GOD BLESS,” written in black marker. She wore a sweater with the hood pulled just above her eyes. Occasionally, she ducked behind the sign, maybe to protect her exposed eyes from the cold Wisconsin weather, or maybe to disappear from the stares of passersby. After about 30 minutes, head down, the woman stood up and walked back to her tent, empty handed except for her sign and bucket.

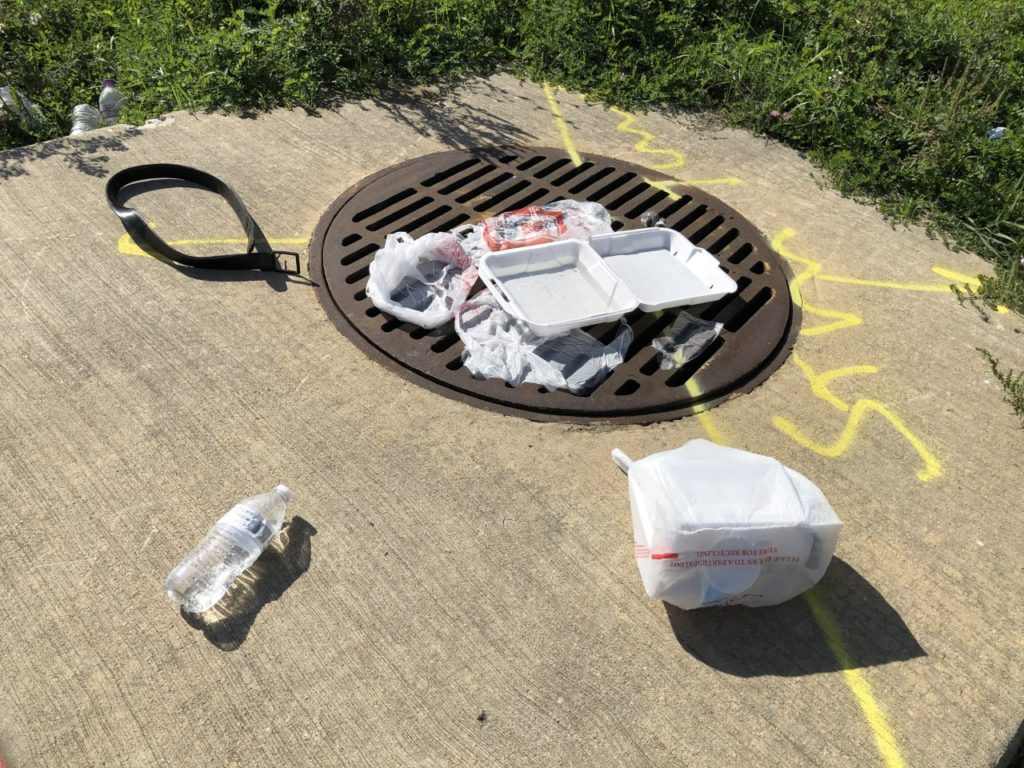

Each person had their own space, distinguished by tents that were unique in color and size. Scattered on the ground were half-eaten bags of chips, styrofoam takeout containers and needles. Drivers passing by either stared at the tents or ignored them. Car horns blared.

“Who’s to say there’s not a person that wants to just drive their car up and run over the people in the tents,” said Antonio Pacheno, a resident of “tent city.”

Pacheno sometimes stood at the same median as the woman. The encampment started to grow throughout the end of 2018. Pacheno first heard about “tent city” around August. It was a popular spot to get change, cash or food from drivers waiting for the light to turn green. He wore a white rosary around his right wrist. As he walked, the reflective cross dangled across his calloused and dry palm. It was given to him by a stranger.

Throughout 2019, long stretches of the I-794 overpass served as a route for daily commuters, and as a roof that sheltered a growing number of homeless individuals. In early October, the state handed out eviction notices to “tent city” residents. By Oct. 31, they had to leave. Many people, including the homeless, wondered where they were supposed to go.

“We want to transition folks with safety and dignity,” said Nicole Angresano, vice president of community impact for the United Way of Greater Milwaukee.

Data Versus Visibility

Milwaukee homeless rates have gradually declined in recent years. From 2009 to 2016, the city’s homeless population dropped from 1,537 to 1,398, according to Milwaukee Point-in-Time Data. Despite lower numbers, the rows of tents that decorate the concrete beneath the overpass have brought attention to the topic. Some think homeless rates are the highest they have ever been. Others believe the large congregations of tents are strategically placed in high traffic areas, as a tactic to bring attention to the needs of tent city residents.

As the city prepares for the 2020 Democratic National Convention, some Milwaukee residents wonder if the eviction notices are an effort to make the city more presentable for visitors ahead of the heightened media focus. Volunteers and relocation workers have offered more than temporary solutions.

“This is really a transition between living on the streets and having permanent housing,” said Angresano.

With $75,000 in funds for relocation efforts, the United Way of Greater Milwaukee offered assistance to homeless individuals who were willing to accept help. The funds were provided by United Way and used for staffing shelters and covering case worker costs. Housing vouchers were made available in addition to United Way’s contribution by the Milwaukee County Housing Division.

“If they don’t want to move then they don’t have to,” said Angresano.

Three tent city residents either opted to stay there or were unfit to receive temporary shelter access after evaluations.

Housing the Homeless

By Oct. 31, 90 “tent city” residents were relocated. Ten individuals, including two couples, were placed in permanent housing, according to Angresano. Since every individual receives a caseworker, an evaluation of the client’s needs takes place before relocation. Assigned caseworkers assist individuals with several aspects of the relocation process.

“The same person helps with all factors,” said James Mathy, administrator of the Milwaukee County Housing Division. “People tend to get lost in government assistance when there are various handoffs.”

Of the homeless who opted for assistance, many were not from the Milwaukee area and it was their first time receiving assistance from the program, Mathy said.

The Housing Division provides vouchers to place qualifying homeless individuals in a neighborhood of their choosing. In 2018, people who resided in two different encampments, including the one in MacArthur Square near the Milwaukee County Courthouse, were could qualify for vouchers. Part of the process includes a mental health evaluation to determine the factors for each person’s shelter needs.

The availability of vouchers fluctuates, however; each community is allocated a number of them based on federal funding and citywide tax levies. The method of relocating individuals into permanent housing is intended to improve relocation success rates.

In a study conducted by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, housing was shown to be more effective for long-term success. About 20 months after shelter entry or random living assignments, permanent housing subsidy families appeared to be doing better than families assigned to community-based rapid re-housing, according to the 2015 Family Options Study. By the year 2025, United Way hopes to end family homelessness in Wisconsin completely.

Increasing Youth Awareness

At Repairers of the Breach, a Milwaukee homeless shelter, music played at the front of a gathering room. Some of the staff danced and sang along when a familiar tune was played on the radio. A few shelter residents joined in and danced in their seats. Others sat patiently in one of the many rows of chairs, waiting for lunch to be served.

The food for the day at Repairers of the Breach was provided by St. Clare Catholic Church. Maureen LeGros, a youth ministry volunteer, drove a group of high schoolers from the suburbs to serve the meal. As she approached the neighborhood near the shelter, LeGros glanced at the students sitting in the back seat of her SUV. Both boys were on their phones, one of them playing a game.

She suggested they put their phones away and look out the window. They stared out at the unfamiliar surroundings. LeGros watched the shocked expressions on their faces as she shifted her eyes from the road to the rear view mirror.

“There’s a different feel down here,” said LeGros. “I want them to notice that.”